注記(区切り記号について)

この翻訳文には、点字に対応させるための区切り記号(マス空け)を入れています。

「|」 … 1マスあけ

「||」 … 2マスあけ

点訳の際に必要となる区切りを、見える形で示しています。

読み進めるうちに、文章のリズムや切れ目を意識していただければ幸いです。

・固有名詞は実際の発音を標準にしますが、日本語で馴染みのあるカタカナ表記を優先しています。

・固有名詞は、原則として最初に登場した時に限って、その固有部分を「第2カギ符」で囲んでいます。

・固有名詞の複合語は、「マス空け」「中点」ではなく、一つの意味のまとまりとして一体性を保つために「第2つなぎ符」で表記しています。

『Brille Editor System ver.8』用の『BESファイル』を、ZIPファイルに圧縮して公開しています。(2025年12月16日現在)

THE BENSON MURDER CASE

S. S. VAN DINE

CHAPTER Ⅱ.

At the Scene of the Crime

||||||||ベンスン|殺人|事件

||||||||S.S.ヴァン_ダイン

||||||第二章

||||事件|現場

(Friday, June 14; 9 a.m.)

(6月|14日|金曜日|午前9時)

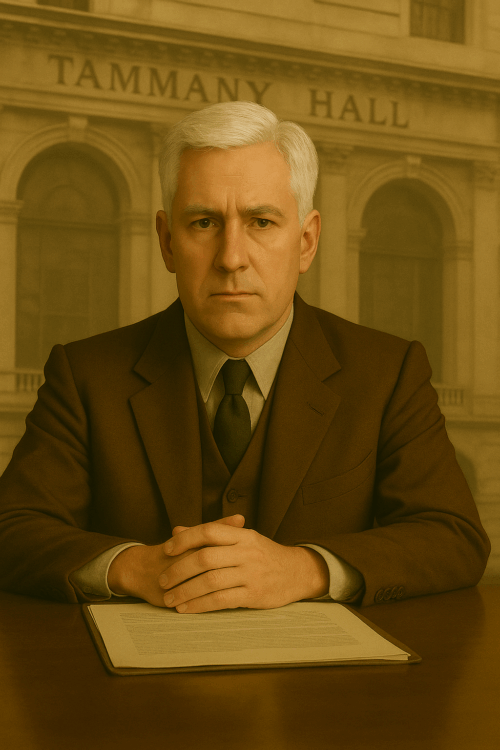

John F.-X. Markham, as you remember, had been elected District Attorney New York County on the Independent Reform Ticket during one of the city’s periodical reactions against Tammany Hall.

He served his four years, and would probably have been elected to a second term had not the ticket been hopelessly split by the political juggling of his opponents.

He was an indefatigable worker, and projected the District Attorney’s office into all manner of criminal and civil investigations.

Being utterly incorruptible, he not only aroused the fervid admiration of his constituents, but produced an almost unprecedented sense of security in those who had opposed him on partisan lines.

<ジョン=F.-X.=マーカム>*1は、|記憶に|あるとおり、|<ニューヨーク_市>で|繰り返し|起こる|<タマニ=ホール>に|対する|周期的な|反動の|際に、|<独立_改革派>から|選ばれた|<ニューヨーク_郡>の|地方|検事|である。

彼は|4年間の|任期を|務めあげたが、|もしも|対立|候補の|政治的な|かけひきで、|改革派の|候補者|名簿の|絶望的な|分裂が|なければ、|おそらく|2期目にも|選ばれていただろう。

彼は|疲れを|知らぬ|働き者で、|<地方_検事局>の|刑事、民事の|あらゆる|調査に|積極的に|乗り出した。

まったく|買収に|屈しない|人物|だったため、|彼は|支持者の|熱烈な|称賛を|呼び起こした|だけでなく、|党派的に|反対する|人たちにさえ、|ほぼ|前例のない|安心感を|与えることが|できた。

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

*1 |ジョン=F.-X.=マーカムの<F.-X.>(Fピリオド||ハイフン|X|ピリオド)は、<Francis Xavier>(フランシス=ザビエル) の|略です。

カトリック|文化圏では、聖人の|名前を|組み合わせる『二重名』が|よく|用いられ、|英語では|その|省略形|として<F.-X.>と|表記される|ことがあります。

したがって、|マーカムの|正式名は|<ジョン=フランシス=ザビエル=マーカム>と考えられます。

He had been in office only a few months when one of the newspapers referred to him as the Watch Dog; and the sobriquet clung to him until the end of his administration.

就任|してから|わずか|数か月の|うちに、|ある|新聞が|彼を|『番犬』と|呼んだ。||そして|その|あだ名は、|彼の|任期が|終わるまで|そう|呼ばれていた。

Indeed, his record as a successful prosecutor during the four years of his incumbency was such a remarkable one that even to-day it is not infrequently referred to in legal and political discussions.

実際、|4年間の|在任中に|達成した|検事としての|業績は|きわめて|顕著なもので、|今日に|いたるまで|法曹界や|政治の|議論で|しばしば|引き合いに|出されるほどだ。

Markham was a tall, strongly-built man in the middle forties, with a clean-shaven, somewhat youthful face which belied his uniformly grey hair.

He was not handsome according to conventional standards, but he had an unmistakable air of distinction, and was possessed of an amount of social culture rarely found in our latter-day political office-holders.

Withal he was a man of brusque and vindictive temperament; but his brusqueness was an incrustation on a solid foundation of good-breeding, not—as is usually the case—the roughness of substructure showing through an inadequately superimposed crust of gentility.

マーカムは|40代|半ばの|背が|高く|がっしりした|体つきの|男で、|ひげを|そった|いくらか|若々しい|顔立ちは、|全体が|灰色の|髪と|そぐわなかった。

彼は、|世間的な|基準でいえば|ハンサムとは|いえなかったが、|まぎれもない|気品を|ただよわせ、|また|近ごろの|政治家には|めったに|見られぬほどの|教養ある|社交性を|身につけていた。

しかも、|彼は|無愛想で|容赦しない|性格の|男だった。

だが、|その|無愛想さは|しっかりした|良家の|育ちの|良さという|基礎の|上に|現れた|外見であり、|よくあるような|上辺だけ|上品さを|纏っただけで、|その下に|乱暴な|部分が|透けて見える|というわけでは|なかった。

When his nature was relieved of the stress of duty and care, he was the most gracious of men.

But early in my acquaintance with him I had seen his attitude of cordiality suddenly displaced by one of grim authority.

It was as if a new personality—hard, indomitable, symbolic of eternal justice—had in that moment been born in Markham’s body.

I was to witness this transformation many times before our association ended.

義務や|ストレス|といった|重圧から|解放|されたとき、|彼は|この上なく|親切で、|愛想の|よい|人物だった。

だが、|知り合って|まもないころ、|私は|彼の|親しげな|態度が、|にわかに|きびしい|威厳へと|すり替わるのを|目にした。

それは|硬い|不屈の|精神と、|そして|永遠の|正義を|象徴|するかのような、|新しい|人格が、|その|瞬間に|マーカムの|体に|宿ったかの|ようだった。

この|交友|関係が|終わるまでに、|私は|この|変貌を|何度も|目の当たりに|することに|なったのだ。

In fact, this very morning, as he sat opposite to me in Vance’s living-room, there was more than a hint of it in the aggressive sternness of his expression; and I knew that he was deeply troubled over Alvin Benson’s murder.

実のところ、|その日の|朝、|まさに、|ヴァンスの|居間で|私の|向かいに|腰をおろした|彼の|表情には、|すでに|攻撃的な|きびしさが|色濃く|ただよっていた。|そして|私は、|<アルヴィン_ベンスン>の|殺人|事件に|彼が|ひどく|心を|悩ませて|いるのを|悟った。

He swallowed his coffee rapidly, and was setting down the cup, when Vance, who had been watching him with quizzical amusement, remarked:

彼は|コーヒーを|あわただしく|飲みほし、|カップを|置こうと|したとき、|ヴァンスが、|おかしそうに|からかうような|まなざしで|彼を|見つめながら、|口をひらいた。

“I say; why this sad preoccupation over the passing of one Benson? You weren’t, by any chance, the murderer, what?”

「おやおや、|なぜまた、|ベンスン|一人が|死んだくらいで、|そんなに|深刻な|顔を|しているんだい?|まさか、|君が|殺したのでは|あるまいね?」

Markham ignored Vance’s levity.

“I’m on my way to Benson’s. Do you care to come along? You asked for the experience, and I dropped in to keep my promise.”

マーカムは、|ヴァンスの|軽口を|聞いてない|ふりをした。

「これから|ベンスンの|家へ|行くところだ。|いっしょに|来るかい?|君が|一度|見てみたいと|言ってたので、|その|約束を|守るために|立ち寄ったんだ。」

I then recalled that several weeks before at the Stuyvesant Club, when the subject of the prevalent homicides in New York was being discussed, Vance had expressed a desire to accompany the District Attorney on one of his investigations; and that Markham had promised to take him on his next important case.

Vance’s interest in the psychology of human behavior had prompted the desire, and his friendship with Markham, which had been of long standing, had made the request possible.

そのとき、|私は|思い出した。|数週間|前、|<スタイヴェサント・クラブ>で、|ニューヨークに|多発する|殺人|事件の|話題が|出ていたとき、|ヴァンスが、|地方|検事に|同行して、|事件の|捜査を|見たいと|伝えていた。|そして、|マーカムが、|次の|重大|事件の|ときには、|必ず|連れて行くと|約束|したことを。

ヴァンスの|人間|行動の|心理学への|興味のため、|その|好奇心が|高まり、|そして|マーカムとの|長年の|友情が、|その願いを|可能にした。

“You remember everything, don’t you?” Vance replied lazily.

“An admirable gift, even if an uncomfortable one.”

He glanced at the clock on the mantel: it lacked a few minutes of nine. “But what an indecent hour! Suppose someone should see me.”

「君は|なんでも|覚えているね?」と、|ヴァンスは|くつろいで|答えた。

「たしかに|立派な|才能だが、|心地悪い|ことでも|あるね。」

彼は|マントルピースの|上の|時計に|目をやった。||九時までに|まだ|数分あった。

「しかし|なんと|不適切な|時刻だ!|誰かに|見られたら|どうする?」

Markham moved forward impatiently in his chair.

“Well, if you think the gratification of your curiosity would compensate you for the disgrace of being seen in public at nine o’clock in the morning, you’ll have to hurry. I certainly won’t take you in dressing-gown and bed-room slippers. And I most certainly won’t wait over five minutes for you to get dressed.”

マーカムは|いすの上で|いら立たしげに|身を|乗り出した。

「まあ、|君が|知りたい|という|好奇心を|満足|させることが、|朝の|九時に|人前に|出るという|不名誉を|埋め合わせ|できると|思うなら、|急いでもらう|しかない。

私は|とても|寝間着に|ガウンと|部屋履き|スリッパ|姿の|君を|連れて行く|気にはなれんよ。

それに、|君が|着がえるのに|五分以上|待つつもりは|まったく|ないからな。」

“Why the haste, old dear?” Vance asked, yawning. “The chap’s dead, don’t y’ know; he can’t possibly run away.”

「ねえ、君。どうして|そんなに|せかすのさ?」と、|ヴァンスは|あくびを|しながら|たずねた。

「だって、|その男は|もう|死んでるんだろ。||逃げ出すはずも|ないじゃないか。」

“Come, get a move on, you orchid,”

the other urged.

“This affair is no joke. It’s damned serious; and from the looks of it, it’s going to cause an ungodly scandal.—What are you going to do?”

「さあ、|さっさと|支度しろよ、|この|上品ぶった|奴め。」と|相手は|せき立てた。

「この件は|冗談ごとじゃ|ないぞ。|とても|重大だし、|見たところ|とんでもない|スキャンダルを|まき起こす|ことに|なりそうだ。||それで、|君は|どうする|つもりだ?」

“Do? I shall humbly follow the great avenger of the common people,” returned Vance, rising and making an obsequious bow.

He rang for Currie, and ordered his clothes brought to him.

“I’m attending a levee which Mr. Markham is holding over a corpse, and I want something rather spiffy. Is it warm enough for a silk suit? . . . And a lavender tie, by all means.”

「どうする|つもりかって?||私は|謹んで|市民の|偉大なる|正義の|味方||マーカムのこと||に|従う|までです」と、|ヴァンスは|答え|立ち上がって|マーカムに|媚びるような|お辞儀を|した。

彼は|カーリーを|呼び、|自分の|服を|持ってくるように|命じた。

「ミスター・マーカムが|死体を|前にして|開く|謁見式に|出るのだから、|ちょっと|洒落た|服装が|いいね。|シルクの|スーツでも|いいくらい|暖かいかな?||それから、|ぜひ|ラヴェンダー|色の|ネクタイを。」

“I trust you won’t also wear your green carnation,” grumbled Markham.

「まさか|緑の|<カーネーション>まで|つけるんじゃ|ないだろうな。」と、|マーカムは|イライラ|しながら|言った。

“Tut! Tut!” Vance chided him.

“You’ve been reading Mr. Hichens. Such heresy in a district attorney!

Anyway, you know full well I never wear boutonnières.

The decoration has fallen into disrepute. The only remaining devotees of the practice are roués and saxophone players. . . . But tell me about the departed Benson.”

「チェッ!」と、ヴァンスは|舌打ちした。

「君は|<ヒチェンズ>||イギリスの|小説家。|『緑のカーネーション』は<オスカー・ワイルド>が|流行らせた|花で、|それを|題材にした|作品||を|読んでるんだな。||地方|検事の|くせに、|そんな|悪趣味を|持ち出すとは!

だいたい|僕は、|ブートニエール||襟に|つける|花飾り||なんて|つけないことを|君も|よく|知ってるだろう。

あんな|飾りは|すっかり|評判が|悪く|なっている。||いまだに|好き好んで|着けているのは、|女たらしと|サックス|奏者|くらいさ。

ところで、|死んだ|ベンスンの|ことについて|聞かせてくれ。」

Vance was now dressing, with Currie’s assistance, at a rate of speed I had rarely seen him display in such matters.

Beneath his bantering pose I recognized the true eagerness of the man for a new experience and one that promised such dramatic possibilities for his alert and observing mind.

ヴァンスは|今や|カーリーに|手伝って|もらいながら、|私が|普段|見たことのない|速さで|着替えていた。

私には、|その|冷やかす|ような|態度の|奥に、|彼が|目新しい|経験を|心から|楽しみに|しているのが|見て取れた。||しかも|それは、|彼の|明晰な|頭脳と|鋭い|観察力を|大いに|発揮できる|劇的な|展開が|期待できる|ものだった。

“You knew Alvin Benson casually, I believe,” the District Attorney said.

“Well, early this morning his housekeeper ’phoned the local precinct station that she had found him shot through the head, fully dressed and sitting in his favorite chair in his living-room.

「君は|アルヴィン・ベンスンと|面識が|あったと|思うが」と、|マーカムが|言った。

「今朝|早く、|彼の|家政婦が、|主人が|頭を|銃で|撃たれて|死んでいるのを|見つけたと、|近くの|警察署に|電話で|知らせて|きたんだ。||服を|着たまま|リビングの|お気に入りの|椅子に|座って|いたそうだ。」

The message, of course, was put through at once to the Telegraph Bureau at Headquarters, and my assistant on duty notified me immediately. I was tempted to let the case follow the regular police routine.

But half an hour later Major Benson, Alvin’s brother, ’phoned me and asked me, as a special favor, to take charge.

その|通報は、|もちろん|ただちに|本部の|通信局へ|回され、|当直の|私の|部下が|すぐさま|私に|知らせてくれた。||私は|当初、|この|事件を|警察の|通常の|手続きに|任せようと|考えていた。

だが|その|30分後、|アルヴィンの|兄|である|ベンスン|少佐が|私に|電話を|かけてきて、|特別に|私に|担当|してほしいと|頼んできた。

I’ve known the Major for twenty years, and I couldn’t very well refuse. So I took a hurried breakfast and started for Benson’s house.

He lived in West Forty-eighth Street; and as I passed your corner I remembered your request, and dropped by to see if you cared to go along.”

私は|少佐とは|20年来の|付き合いで、|とても|断る|わけには|いかなかった。

そこで|急いで|朝食を|済ませ、|ベンスンの|家へと|向かった。

彼は|西|48丁目に|住んでいたが、|君の|家の|角を|通りかかった。|そこで|ふと|君の|頼みを|思い出して、|一緒に|行くか|どうか|確かめようと|立ち寄ったのさ。」

“Most consid’rate,” murmured Vance, adjusting his four-in-hand before a small polychrome mirror by the door. Then he turned to me.

“Come, Van. We’ll all gaze upon the defunct Benson. I’m sure some of Markham’s sleuths will unearth the fact that I detested the bounder and accuse me of the crime; and I’ll feel safer, don’t y’ know, with legal talent at hand. . . . No objections—eh, what, Markham?”

「それは|ご親切な|ことで」と、ヴァンスは、|扉の|脇に|ある|飾り付きの|小さな|鏡の|前で、|ネクタイの|<プレーン|ノット>||一般的な|1回|結び||の|結び目を|直しながら|つぶやいた。||それから|彼は|私の方を|振り向いた。

「ヴァン、|君も|来てくれ。||二人で|亡くなった|ベンスンの|顔を|拝みに|行くことに|しよう。||きっと|マーカムの|部下の|刑事どもが、|僕が|あの|成金|男を|嫌って|いたことを|嗅ぎつけて、|僕を|犯人に|仕立て上げるに|ちがいない。||だから|法律家の|君が|そばに|いた方が|安心|ということで、|異論は|ないよね、|マーカム?」

“Certainly not,” the other agreed readily, although I felt that he would rather not have had me along. But I was too deeply interested in the affair to offer any ceremonious objections, and I followed Vance and Markham downstairs.

「もちろん、|異論は|ない」と|マーカムは|すぐに|応じて|くれたが、|内心では|私が|同行|するのを|快く|思って|いないように|感じられた。

それでも|私は|事件に|強く|惹かれて|いたので、|とても|改って|遠慮する|気には|なれず、|ヴァンスと|マーカムの|あとに|ついて|1階へ|降りていった。

As we settled back in the waiting taxicab and started up Madison Avenue, I marvelled a little, as I had often done before, at the strange friendship of these two dissimilar men beside me—Markham forthright, conventional, a trifle austere, and over-serious in his dealings with life; and Vance casual, mercurial, debonair, and whimsically cynical in the face of the grimmest realities.

待たせてあった|タクシーに|腰を|落ち着け、|車が|<マディソン・アヴェニュー>を|走り出すと、|私は|これまでにも|幾度となく|そう|感じて|きたように、|隣に|並ぶ|まったく|対照的な|二人の|間に|結ばれた|奇妙な|友情に、|改めて|驚かされた。

マーカムは|率直で、|常識的、|やや|堅苦しく、|いき方に|ついて|あまりにも|真面目すぎる|性格だった。

一方|ヴァンスは、|気ままな|気分屋で|愛想がよく、|どんなに|深刻な|現実を|前にしても、|どこか|奇妙な|皮肉屋だった。

And yet this temperamental diversity seemed, in some wise, the very cornerstone of their friendship: it was as if each saw in the other some unattainable field of experience and sensation that had been denied himself.

Markham represented to Vance the solid and immutable realism of life, whereas Vance symbolized for Markham the care-free, exotic, gypsy spirit of intellectual adventure.

Their intimacy, in fact, was even greater than showed on the surface; and despite Markham’s exaggerated deprecations of the other’s attitudes and opinions, I believe he respected Vance’s intelligence more profoundly than that of any other man he knew.

それにも|かかわらず、|この|性格の|違いこそが、|ある|意味では|まさに|彼らの|友情の|礎で|あるように|思われた。||まるで|互いに|相手の|中に、|自分|自身には|備わって|いない、|手の|届かぬ|経験や|感覚の|領域を|見ているかの|ようだった。

マーカムは|ヴァンスに|とって、|人生の|揺るぎない|現実|そのものを|体現する|存在だった。||一方で、|ヴァンスは|マーカムに|とって、|気ままで|風変わりな|知的|冒険を|楽しむ|自由人|気質の|象徴だった。

実際には、|二人の|親密な|関係は|見かけ|以上だった。||マーカムは|ヴァンスの|態度や|考え方を|大げさに|否定|してみせる|ことが|多かったが、|心の底では、|彼を|知っている|他の|誰よりも|ヴァンスの|知性を|高く|評価|していたのだと|私は|思っている。

As we rode up town that morning Markham appeared preoccupied and gloomy. No word had been spoken since we left the apartment; but as we turned west into Forty-eighth Street Vance asked:

その|朝、|タクシーで|<アップ|タウン>||マンハッタン|島の|北側の|地域を|指す|呼び方||方面へ|向かうあいだ、|マーカムは|思いつめた|ように|暗い|表情を|していた。||アパートを|出てから|一言も|言葉を|交わさ|なかったが、|やがて|48丁目を|西に|折れたとき、|ヴァンスが|口を|開いた。

“What is the social etiquette of these early-morning murder functions, aside from removing one’s hat in the presence of the body?”

こんな|朝っぱらの|殺人|現場での|社交的な|マナーは|何か|あるのかな?||せめて|遺体の|前では|帽子を|とるくらいは|別に|してさ。

“You keep your hat on,” growled Markham.

「帽子なんか|脱がなくていい、|かぶってろ。」

マーカムが|怒鳴るように|言った。

“My word! Like a synagogue, what? Most int’restin’! Perhaps one takes off one’s shoes so as not to confuse the footprints.”

「これは|驚いた!||まるで|ユダヤ教の|礼拝堂|みたいじゃないか。||いやはや|興味深いね!||足跡が|混ざらない|ように、|靴を|脱ぐ|決まりでも|あるのかな。」

“No,” Markham told him. “The guests remain fully clothed—in which the function differs from the ordinary evening affairs of your smart set.”

「脱がない」と、|マーカムが言った。

「ここでは|皆んな|服も|着たままだ。||そのあたりは|君の|気取った|仲間|たちとの|夜の|集とは|違うんだ。」

“My dear Markham!”—Vance’s tone was one of melancholy reproof—“The horrified moralist in your nature is at work again. That remark of yours was pos’tively Epworth Leaguish.”

「やれやれ、マーカム!」

ヴァンスは|憐れむような|口調で|不満げに|言った。

「また、|君の|中の|堅苦しい|道徳観が|顔を出したね。||今の|君の|発言は、|まるで<エプワース>同盟||禁酒、|禁欲など|厳格な|道徳|規律を|重んじた|キリスト教の|青年|組織||みたいだよ。

Markham was too abstracted to follow up Vance’s badinage.

マーカムは|ぼんやりと|考えごとを|しているのか、|ヴァンスの|軽口は|相手に|しなかった。

“There are one or two things,” he said soberly, “that I think I’d better warn you about. From the looks of it, this case is going to cause considerable noise, and there’ll be a lot of jealousy and battling for honors.

I won’t be fallen upon and caressed affectionately by the police for coming in at this stage of the game; so be careful not to rub their bristles the wrong way.

My assistant, who’s there now, tells me he thinks the Inspector has put Heath in charge. Heath’s a sergeant in the Homicide Bureau, and is undoubtedly convinced at the present moment that I’m taking hold in order to get the publicity.”

「ちょっと|忠告して|おいた方が|いいことが|二つ|三つある。」

マーカムは|真剣な|声で|言った。

「この|事件は、|どうやら|相当な|騒ぎに|なりそうだ。||それに|手柄|争いや|出し抜き、|それに|伴う|嫉みなど、|あちこちで|起こるだろう。

この|段階で|私が|事件に|顔を|出したところで、|警察が|心よく|歓迎|してくれる|わけじゃない。||だから|警察の|気に|障るような|真似は|しないように|注意|してくれ。

今、|現場に|いる|私の|部下の|話では、|警部||警察の|複数の|分署を|統括する|高級|幹部||は|<ヒース>を|担当に|据えたらしい。||ヒースは|殺人課の|巡査|部長で、|きっと|今ごろ、|私が|事件を|引き受けようと|しているのは|売名|目的だと|決めつけて|いるに|違いない。」

“Aren’t you his technical superior?” asked Vance.

「君は|制度的には、|彼より|上の|立場では|ないのか?」と、|ヴァンスが|聞いた。

“Of course; and that makes the situation just so much more delicate. . . . I wish to God the Major hadn’t called me up.”

「もちろん|そうだ。||だからこそ、|事態は|いっそう|ややこしくなる。||まったく、|大佐が|私に|電話なんか|してこなければ|よかったと|思うくらいだ。」

“Eheu!” sighed Vance. “The world is full of Heaths. Beastly nuisances.”

「ああ!」と|ヴァンスは|ため息を|ついた。

「世の中には|ヒースのような|奴が|ごまんと|いる。まったく|厄介な|連中だ。」

“Don’t misunderstand me,” Markham hastened to assure him.

“Heath is a good man—in fact, as good a man as we’ve got. The mere fact that he was assigned to the case shows how seriously the affair is regarded at Headquarters. There’ll be no unpleasantness about my taking charge, you understand; but I want the atmosphere to be as halcyon as possible.

Heath’ll resent my bringing along you two chaps as spectators, anyway; so I beg of you, Vance, emulate the modest violet.”

「誤解して|くれるなよ」と、|マーカムは|あわてて|念を|押した。

「ヒースは|優秀な|奴だ。||実際、|我々の|中では|最高の|人物と|言っていい。||今回|彼が|担当に|なった|事実|自体が、|本部が|この|事件を|いかに|重く|見ているかを|示している。

君たちも|理解|しておいて|欲しい。||私が|指揮|とることで|トラブルに|なることは|ないと|思うが、|できるだけ|穏やかな|雰囲気に|しておきたい。

ヒースは、|君たち|二人を|見物人|として|連れて行くと、|いずれにせよ|ひどく|嫌がると|思う。||だから|頼むよ|ヴァンス、|慎ましく|すみれの|花にでも|なっていてくれ。」

“I prefer the blushing rose, if you don’t mind,” Vance protested.

“However, I’ll instantly give the hypersensitive Heath one of my choicest Régie cigarettes with the rose-petal tips.”

「僕はね、|控えめな|すみれよりも、|はにかんで|顔を|赤らめた|バラの方が|好みなんんだが、|それで|よろしいかな?」と|ヴァンスは|言い返した。

「それでは|さっそく、|神経|過敏な|ヒースには、|僕の|とっておきの|<レジー・シガレット>||フランスの|高級|タバコ||を|1本|差し上げると|しよう。||吸い口に|バラの|花びらが|ついてるんだ。」

“If you do,” smiled Markham, “he’ll probably arrest you as a suspicious character.”

「そんなことを|したらな」と、|マーカムは|笑った。

「ヒースは|きっと|君を、|不審|人物として|逮捕|するだろうよ。」

We had drawn up abruptly in front of an old brownstone residence on the upper side of Forty-eighth Street, near Sixth Avenue. It was a house of the better class, built on a twenty-five-foot lot in a day when permanency and beauty were still matters of consideration among the city’s architects.

The design was conventional, to accord with the other houses in the block, but a touch of luxury and individuality was to be seen in its decorative copings and in the stone carvings about the entrance and above the windows.

私たちの|乗った|車は、|48丁目の|6番街|近く、|通りの|北側に|ある|古い|ブラウン|ストーン||19世紀に|ニューヨークで|流行した|茶色の|石を|使った|建築|様式||の|建物の|前で、|突然|止まった。

それは|間口|25フィート||約|7.6メートル||の|屋敷で、|まだ|都市の|建築家|たちが、|耐久性と|美しさを|重んじていた|時代に|建てられた|ものだった。

その|設計は、|ごく|ありふれた|もので、|その|区画の|ほかの|家並と|調和していた。|

だが、|壁や|屋根の|装飾や、|入口や|窓の|上に|施された|石彫りには、|多少の|贅沢さと|独自性が|見られた。|

There was a shallow paved areaway between the street line and the front elevation of the house; but this was enclosed in a high iron railing, and the only entrance was by way of the front door, which was about six feet above the street level at the top of a flight of ten broad stone stairs.

Between the entrance and the right-hand wall were two spacious windows covered with heavy iron grilles.

家の|正面と|通りとの|間には、|狭い|舗装された|通路|が|あった。|

だが、|そこは|高い|鉄の|手すりに|囲まれており、|地下|勝手口は|なく、|入口は|唯一|10段の|幅広い|石の|階段を|上がった|6フィート||約|1.8メートル||ほど|通りから|高くなった|玄関から|入るしか|なかった。

玄関と|右側の|壁との|間には、|二つの|大きな|窓が|あるが、|頑丈な|鉄格子が|はめられていた。

A considerable crowd of morbid onlookers had gathered in front of the house; and on the steps lounged several alert-looking young men whom I took to be newspaper reporters.

The door of our taxicab was opened by a uniformed patrolman who saluted Markham with exaggerated respect and ostentatiously cleared a passage for us through the gaping throng of idlers.

家の|前には、|かなりの|数の|ヤジ馬が|集まっていた。

玄関の|石段には、|数人の|若い|男たちが|腰を|下ろしたり|ぶらぶら|していたが、|その目は|鋭く|注意深かった。||私は|彼らを|新聞|記者と|受け取った。

タクシーの|ドアを|開けたのは|制服の|巡査で、|彼は|マーカムに|大げさなほど|恭しく|敬礼すると、|わざとらしく|私たちのために|道を|開けた。|

その道は、|ぽかんと|口をあけている|野次馬の|群衆の|中に|通じていた。

Another uniformed patrolman stood in the little vestibule, and on recognizing Markham, held the outer door open for us and saluted with great dignity.

もう一人の|制服|警官が|小さな|玄関に|立っていた。|

彼は|マーカムに|気づくと、|私たちの|ために|扉を|開けてまま、|いかにも|重々しく|敬礼した。

“Ave, Cæsar, te salutamus,” whispered Vance, grinning.

「<カエサル>|万歳」と、ヴァンスが|笑いながら|ささやいた。

“Be quiet,” Markham grumbled.

“I’ve got troubles enough without your garbled quotations.”

「黙ってろ」と、|マーカムが|不満げに|言った。

「君の|デタラメな|例え話に|付き合うほど、|今は|暇じゃないんだ。」

As we passed through the massive carved-oak front door into the main hallway, we were met by Assistant District Attorney Dinwiddie, a serious, swarthy young man with a prematurely lined face, whose appearance gave one the impression that most of the woes of humanity were resting upon his shoulders.

私たちは、|重厚な|彫刻の|入った|オーク_材の|正面|扉を|抜けると|広い|ホールに|入った。

そこで|出迎えたのは、|地方_検事補の|<ディンウィディ>だった。

浅黒い|肌に、|若いにも|関わらず|皺の|刻まれた|真面目そうな|顔つきを|しており、|まるで|人類の|あらゆる|悲哀を|その|肩に|背負っているかの|ような|印象を|与える|男だった。

“Good morning, Chief,” he greeted Markham, with eager relief.

“I’m damned glad you’ve got here. This case’ll rip things wide open. Cut-and-dried murder, and not a lead.”

「おはようございます、|チーフ」と、|彼は|ほっとしたように|勢いよく|マーカムに|声をかけた。

「来てくださって|本当に|助かりました。||この|事件は|大騒動に|なりますよ。||ありふれた|殺人|なんですが、|手がかりが|まるっきり|ないんです。」

Markham nodded gloomily, and looked past him into the living-room.

マーカムは|深刻そうに|うなずき、|彼の|肩越しに|広い|部屋の|中を|見回した。

“Who’s here?” he asked.

「誰が|来てる?」と、|彼は|尋ねた。

“The whole works, from the Chief Inspector down,” Dinwiddie told him, with a hopeless shrug, as if the fact boded ill for all concerned.

「勢揃いですよ。|主任警部から|下っ端まで」と、|ディンウィディは|肩を|すくめて、|まるで、|そのこと|自体が|関係者|全員に|とって|悪い兆しの|ように|言った。

At that moment a tall, massive, middle-aged man with a pink complexion and a closely-cropped white moustache, appeared in the doorway of the living-room. On seeing Markham he came forward stiffly with outstretched hand. I recognized him at once as Chief Inspector O’Brien, who was in command of the entire Police Department.

そのとき、|広い|部屋の|入口に、|背が|高く、|がっしりした|中年の|男が|現れた。

血色のよい|顔に、|短く|刈りそろえた|白い|口髭を|たくわえている。

彼は|マーカムを|見るなり、|姿勢を|正して|手を|差し出しながら|歩み寄った。

私は|すぐに、|それが|警察|全体を|統括する|<

主任_警部の|<オブライエン>だと|わかった。

Dignified greetings were exchanged between him and Markham, and then Vance and I were introduced to him. Inspector O’Brien gave us each a curt, silent nod, and turned back to the living-room, with Markham, Dinwiddie, Vance and myself following.

マーカムと|オブライエンの|あいだで、|重々しい|挨拶が|交わされた。

つづいて|ヴァンスと|私が|紹介されると、|オブライエン|主任_警部は|私たちに|短く|無言の|うなずきを|返し、|そのまま|広い|部屋へ|向き直った。

マーカム、|ディンウィディ、|ヴァンス、|そして|私が|そのあとに|続いた。

The room, which was entered by a wide double door about ten feet down the hall, was a spacious one, almost square, and with high ceilings.

Two windows gave on the street; and on the extreme right of the north wall, opposite to the front of the house, was another window opening on a paved court. To the left of this window were the sliding doors leading into the dining-room at the rear.

その|部屋は、|廊下を|十フィートほど|進んだ先の、|幅の|広い|両開きの|扉から|入るように|なっていた。

広々として|ほとんど|正方形に|近く、|天井も|高い。

通りに|面した|窓が|二つあり、|北側の|壁の|いちばん|右手|、つまり|家の|正面とは|反対側には、|石畳の|中庭に|面した|もう一つの|窓があった。

その|窓の|左側には、|奥の|食堂へ|通じる|引き戸が|設けられていた。

The room presented an appearance of garish opulence.

About the walls hung several elaborately framed paintings of race-horses and a number of mounted hunting trophies.

A highly-colored oriental rug covered nearly the entire floor.

In the middle of the east wall, facing the door, was an ornate fireplace and carved marble mantel.

Placed diagonally in the corner on the right stood a walnut upright piano with copper trimmings.

その|部屋は、|けばけばしい|ほどの|豪華さを|放っていた。

壁には、|豪華な|額縁に|収められた|数枚の|競走馬の|絵と、|いくつもの|狩猟の|戦利品が|飾られていた。

床|全体は、|きわめて|鮮やかな|東洋の|絨毯が|敷き詰められていた。

東の|壁の|中央、|つまり|入って|正面には、|装飾を|凝らした|暖炉と、|彫刻の|施された|大理石の|マントルピースが|あった。

右手の|隅には、|クルミ_材の|アップライト・ピアノが|斜めに|置かれ、|銅の|装飾で|縁取られていた。

Then there was a mahogany bookcase with glass doors and figured curtains, a sprawling tapestried davenport, a squat Venetian tabouret with inlaid mother of pearl, a teak-wood stand containing a large brass samovar, and a buhl-topped center table nearly six feet long.

その|ほかにも、|ガラス|扉と|模様入りの|カーテンを|備えた|マホガニーの|書棚。|横たわることが|できるほど|大きな|タペストリー|張りの|ソファ。||螺鈿|細工を|ほどこした|脚の|短い|ヴェネツィア_風の|スツール||背もたれのない|装飾用の|椅子||。||大きな|真鍮製の|サモワール||ロシアで|使われる|卓上|湯沸かし器||を|載せた|チーク_材の|台。||そして|長さ|六フィート|近い|ブール|細工(フランス|<ルイ14世>時代の|家具|職人|<ブール>の|様式)の|天板を|持つ|センターテーブルが|置かれていた。

At the side of the table nearest the hallway, with its back to the front windows, stood a large wicker lounge chair with a high, fan-shaped back.

この|テーブルの|いちばん|廊下に|近い方で、|正面の|窓に|背を向けた|位置に、|背もたれが|扇形に|高く|広がった、|枝で編んだ|大きな|安楽|椅子が|置かれていた。

In this chair reposed the body of Alvin Benson.

その|椅子に、|<アルヴィン=ベンスン>の|遺体が|横たわっていた。

Though I had served two years at the front in the World War and had seen death in many terrible guises, I could not repress a strong sense of revulsion at the sight of this murdered man. In France death had seemed an inevitable part of my daily routine, but here all the organisms of environment were opposed to the idea of fatal violence.

第一次|大戦で|二年間、|前線|勤務を|経験し、|あらゆる|凄惨な|形の|死を|見てきた|私|だったが、|この|殺された|男を|目にしたときには、|どうしても|激しい|嫌悪の|感情を|抑えることが|できなかった。

フランスでは、|<死>は|日常の|一部として|当然の|ように|存在|していた。

だが|ここでは、|周囲の|すべてが、|致命的な|暴力という|概念からは|その|対局に|あるように|思えたのだ。

The bright June sunshine was pouring into the room, and through the open windows came the continuous din of the city’s noises, which, for all their cacophony, are associated with peace and security and the orderly social processes of life.

明るい|六月の|太陽の|光が|部屋|いっぱいに|差し込み、|開け放たれた|窓からは、|都会の|ざわめきが|絶え間なく|流れ込んでくる。

その|騒音の|入り混じった|雑踏の|中にも、|どこか|平和と|安定、|そして|社会|生活の|秩序ある|営みを|思わせる|響きがあった。

Benson’s body was reclining in the chair in an attitude so natural that one almost expected him to turn to us and ask why we were intruding upon his privacy.

His head was resting against the chair’s back. His right leg was crossed over his left in a position of comfortable relaxation.

His right arm was resting easily on the center-table, and his left arm lay along the chair’s arm.

But that which most strikingly gave his attitude its appearance of naturalness, was a small book which he held in his right hand with his thumb still marking the place where he had evidently been reading.5

ベンスンの|死体は|椅子に|もたれかかる|ように|座っていた。

その姿勢が|あまりにも|自然|だったので、|我々が|彼の|部屋に|立ち入ったのか|理由を|尋ねるために、|今にも|振り向くのでは|ないかと|思われる|ほどだった。

彼の|頭は|椅子の|背に|もたれていた。||右脚は|左脚の|上に|組まれ、|いかにも|楽に|くつろいだ|姿勢だった。

彼の|右腕は|センターテーブルの|上に|だらりと|置かれ、|左腕は|椅子の|肘掛けに|沿って|伸ばされていた。

だが、|彼の|姿勢を|とりわけ|自然なものに|見せていたのは、|右手に|持っている|小さな|本|であり、|親指が|つい|先ほどまで|読んでいた|箇所を|押さえたままに|なっていた。

He had been shot through the forehead from in front; and the small circular bullet mark was now almost black as a result of the coagulation of the blood.

A large dark spot on the rug at the rear of the chair indicated the extent of the hemorrhage caused by the grinding passage of the bullet through his brain.

Had it not been for these grisly indications one might have thought that he had merely paused momentarily in his reading to lean back and rest.

彼は|正面から|額を|撃ち抜かれており、|小さな|円形の|弾痕は、|血液が|固まって、|いまでは|ほとんど|黒ずんで|見えた。

椅子の|背後の|絨毯には|大きな|黒い|染みが|あり、|弾丸が|脳を|えぐり抜けた|ことで|生じた|出血の|激しさを|表していた。

こうした|陰惨な|痕跡が|なかったなら、|彼は|読書の|途中で|ほんの|ひととき|手を|休め、|椅子に|もたれて|休んでいる|だけだと|思われたかも|しれない。

He was attired in an old smoking-jacket and red felt bed-room slippers, but still wore his dress trousers and evening shirt, though he was collarless, and the neck band of the shirt had been unbuttoned as if for comfort.

He was not an attractive man physically, being almost completely bald and more than a little stout.

His face was flabby, and the puffiness of his neck was doubly conspicuous without its confining collar.

With a slight shudder of distaste I ended my brief contemplation of him, and turned to the other occupants of the room.

彼は|年季の|入った|スモーキング=ジャケット(室内用の|ベルベットなどの|洒落た|上着)に|赤い|フェルトの|寝室用|スリッパを|履いていたが、|ズボンは|正装用の|ままで、|夜会用|シャツも|着たままだった。||ただし襟は|外され、|シャツの|首回りの|バンドは、|楽に|なるためか、|外されていた。

彼は|容貌の|点では|魅力的とは|言えず、|ほとんど|禿げ上がっていて、|しかも|かなり|太り気味|だった。||彼の|顔は|たるみがちで、|首元は、|締め付ける|襟が|ないために、|むくんだ|様子が|いっそう|目立っていた。

私は、|少し|嫌気がさして|身震いすると、|彼を|観察|するのは|すぐに|打ち切って、|部屋の|ほかの|居合わせた|者たちの|ほうへと|目を向けた。

Two burly fellows with large hands and feet, their black felt hats pushed far back on their heads, were minutely inspecting the iron grill-work over the front windows.

They seemed to be giving particular attention to the points where the bars were cemented into the masonry; and one of them had just taken hold of a grille with both hands and was shaking it, simian-wise, as if to test its strength.

Another man, of medium height and dapper appearance, with a small blond moustache, was bending over in front of the grate looking intently, so it seemed, at the dusty gas-logs.

On the far side of the table a thickset man in blue serge and a derby hat, stood with arms a-kimbo scrutinizing the silent figure in the chair.

His eyes, hard and pale blue, were narrowed, and his square prognathous jaw was rigidly set.

He was gazing with rapt intensity at Benson’s body, as though he hoped, by the sheer power of concentration, to probe the secret of the murder.

手足の|大きい|がっしりした|男が|二人、|黒い|フェルト帽を|深く|後ろへ|ずらし、|正面の|窓に|取り付けられた|鉄製の|格子を|細かい|ところまで|念入りに|調べていた。

彼らは、|とりわけ|格子が|石積みの|セメントに|固定|されている|箇所に|注意を|向けている|ようで、|そのうちの|一人は、|ちょうど|両手で|格子を|つかみ|猿のような|身ぶりで|揺さぶって、|その強度を|確かめていた。

もう一人の|中肉|中背の|男は、|小ぎれいな|身なりで|金色の|小さな|口ひげを生やし、|暖炉の|前に|身をかがめ、|みをかげめ|ほこりを|かぶった|ガス|暖炉の|薪の|飾りを、|じっと|見つめている|ようだった。

テーブルの|向こう側では、|青い|サージの|服に|山高帽を|かぶった|がっしりした|男が、|両手を|腰に|当てた|姿勢で、|椅子に|座る|無言の|人物を|じっと|見据えていた。

彼の|厳しく|淡い|青色の|目は|細められ、|四角ばって|突き出た|下顎は、|きつく|据えられていた。

彼は、|まるで|集中力|そのものの|力で|殺人の|秘密を|見抜こうとでも|するかのように、|ベンスンの|遺体を、|息をのむほど|じっと|凝視していた。

Another man, of unusual mien, was standing before the rear window, with a jeweller’s magnifying glass in his eye, inspecting a small object held in the palm of his hand.

From pictures I had seen of him I knew he was Captain Carl Hagedorn, the most famous fire-arms expert in America.

He was a large, cumbersome, broad-shouldered man of about fifty; and his black shiny clothes were several sizes too large for him. His coat hitched up behind, and in front hung half way down to his knees; and his trousers were baggy and lay over his ankles in grotesquely comic folds. His head was round and abnormally large, and his ears seemed sunken into his skull. His mouth was entirely hidden by a scraggly, grey-shot moustache, all the hairs of which grew downwards, forming a kind of lambrequin to his lips. Captain Hagedorn had been connected with the New York Police Department for thirty years, and though his appearance and manner were ridiculed at Headquarters, he was profoundly respected. His word on any point pertaining to fire-arms and gunshot wounds was accepted as final by Headquarters men.

Another man, of unusual mien, was standing before the rear window, with a jeweller’s magnifying glass in his eye, inspecting a small object held in the palm of his hand. From pictures I had seen of him I knew he was Captain Carl Hagedorn, the most famous fire-arms expert in America. He was a large, cumbersome, broad-shouldered man of about fifty; and his black shiny clothes were several sizes too large for him. His coat hitched up behind, and in front hung half way down to his knees; and his trousers were baggy and lay over his ankles in grotesquely comic folds. His head was round and abnormally large, and his ears seemed sunken into his skull. His mouth was entirely hidden by a scraggly, grey-shot moustache, all the hairs of which grew downwards, forming a kind of lambrequin to his lips. Captain Hagedorn had been connected with the New York Police Department for thirty years, and though his appearance and manner were ridiculed at Headquarters, he was profoundly respected. His word on any point pertaining to fire-arms and gunshot wounds was accepted as final by Headquarters men.

In the rear of the room, near the dining-room door, stood two other men talking earnestly together. One was Inspector William M. Moran, Commanding Officer of the Detective Bureau; the other, Sergeant Ernest Heath of the Homicide Bureau, of whom Markham had already spoken to us.

As we entered the room in the wake of Chief Inspector O’Brien everyone ceased his occupation for a moment and looked at the District Attorney in a spirit of uneasy, but respectful, recognition. Only Captain Hagedorn, after a cursory squint at Markham, returned to the inspection of the tiny object in his hand, with an abstracted unconcern which brought a faint smile to Vance’s lips.

Inspector Moran and Sergeant Heath came forward with stolid dignity; and after the ceremony of hand-shaking (which I later observed to be a kind of religious rite among the police and the members of the District Attorney’s staff), Markham introduced Vance and me, and briefly explained our presence. The Inspector bowed pleasantly to indicate his acceptance of the intrusion, but I noticed that Heath ignored Markham’s explanation, and proceeded to treat us as if we were non-existent.

Inspector Moran was a man of different quality from the others in the room. He was about sixty, with white hair and a brown moustache, and was immaculately dressed. He looked more like a successful Wall Street broker of the better class than a police official.6

“I’ve assigned Sergeant Heath to the case, Mr. Markham,” he explained in a low, well-modulated voice. “It looks as though we were in for a bit of trouble before it’s finished. Even the Chief Inspector thought it warranted his lending the moral support of his presence to the preliminary rounds. He has been here since eight o’clock.”

Inspector O’Brien had left us immediately upon entering the room, and now stood between the front windows, watching the proceedings with a grave, indecipherable face.

“Well, I think I’ll be going,” Moran added. “They had me out of bed at seven-thirty, and I haven’t had any breakfast yet. I won’t be needed anyway now that you’re here. . . . Good-morning.” And again he shook hands.

When he had gone Markham turned to the Assistant District Attorney.

“Look after these two gentlemen, will you, Dinwiddie? They’re babes in the wood, and want to see how these affairs work. Explain things to them while I have a little confab with Sergeant Heath.”

Dinwiddie accepted the assignment eagerly. I think he was glad of the opportunity to have someone to talk to by way of venting his pent-up excitement.

As the three of us turned rather instinctively toward the body of the murdered man—he was, after all, the hub of this tragic drama—I heard Heath say in a sullen voice:

“I suppose you’ll take charge now, Mr. Markham.”

Dinwiddie and Vance were talking together, and I watched Markham with interest after what he had told us of the rivalry between the Police Department and the District Attorney’s office.

Markham looked at Heath with a slow gracious smile, and shook his head.

“No, Sergeant,” he replied. “I’m here to work with you, and I want that relationship understood from the outset. In fact, I wouldn’t be here now if Major Benson hadn’t ’phoned me and asked me to lend a hand. And I particularly want my name kept out of it. It’s pretty generally known—and if it isn’t, it will be—that the Major is an old friend of mine; so, it will be better all round if my connection with the case is kept quiet.”

Heath murmured something I did not catch, but I could see that he had, in large measure, been placated. He, in common with all other men who were acquainted with Markham, knew his word was good; and he personally liked the District Attorney.

“If there’s any credit coming from this affair,” Markham went on, “the Police Department is to get it; therefore I think it best for you to see the reporters. . . . And, by the way,” he added good-naturedly, “if there’s any blame coming, you fellows will have to bear that, too.”

“Fair enough,” assented Heath.

“And now, Sergeant, let’s get to work,” said Markham.

5

The book was O. Henry’s Strictly Business, and the place at which it was being held open was, curiously enough, the story entitled “A Municipal Report.”

その本は|<O=ヘンリー>の|『完璧な|お仕事』(政治や|ビジネスを|題材に、|事務的な|言葉遣いの|裏に|皮肉を|込めた|短編集)で、|しかも|奇妙なことに、|開かれていた|箇所は|『市町村|広報』と|題された|箇所だった。