注記(区切り記号について)

この翻訳文には、点字に対応させるための区切り記号(マス空け)を入れています。

「|」 … 1マスあけ

「||」 … 2マスあけ

点訳の際に必要となる区切りを、見える形で示しています。

読み進めるうちに、文章のリズムや切れ目を意識していただければ幸いです。

注記(区切り記号について)

この翻訳文には、点字に対応させるための区切り記号(マス空け)を入れています。

「|」 … 1マスあけ

「||」 … 2マスあけ

点訳の際に必要となる区切りを、見える形で示しています。

読み進めるうちに、文章のリズムや切れ目を意識していただければ幸いです。

『Brille Editor System ver.8』用の『BESファイル』を、ZIPファイルに圧縮して公開しています。(2025年11月23日現在)

・固有名詞は英語の実際の発音を標準にしますが、日本語で馴染みのあるカタカナ表記を優先しています。

・固有名詞は、原則として最初に登場した時に限って、その固有部分を「第2カギ符」で囲んでいます。

・固有名詞の複合語は、「マス空け」「中点」ではなく、一つの意味のまとまりとして一体性を保つために「第2つなぎ符」で表記しています。

THE BENSON MURDER CASE

S. S. VAN DINE

CHAPTER I.

Philo Vance at Home

||||||||ベンスン|殺人|事件

||||||||S.|S.|ヴァン=ダイン

||||||第一章

||||<フィロ=ヴァンス>の|部屋にて

(Friday, June 14; 8.30 a.m.)

It happened that, on the morning of the momentous June the fourteenth when the discovery of the murdered body of Alvin H. Benson created a sensation which, to this day, has not entirely died away, I had breakfasted with Philo Vance in his apartment. It was not unusual for me to share Vance’s luncheons and dinners, but to have breakfast with him was something of an occasion. He was a late riser, and it was his habit to remain incommunicado until his midday meal.

(6月|14日|金曜日|午前|8時|30分)

<アルヴィン=ベンスン>の|殺害された|死体が|発見され、|その|衝撃が|いまなお|完全には|消え去って|いない|あの|運命の|日、|6月|14日の|朝の|ことだった。||私は|フィロ=ヴァンスの|アパートで|朝食を|ともにしていた。||ヴァンスと|昼食や|夕食を|共にする|ことは|珍しく|なかったが、|朝食と|なると|話は|別だった。||彼は|朝は|苦手な|方で、|正午までは|人と|会わないのを|習慣に|していたからだ。

The reason for this early meeting was a matter of business—or, rather, of æsthetics. On the afternoon of the previous day Vance had attended a preview of Vollard’s collection of Cézanne water-colors at the Kessler Galleries, and having seen several pictures he particularly wanted, he had invited me to an early breakfast to give me instructions regarding their purchase.

この|珍しい|朝食の|わけは、|仕事上、|いや、|むしろ|仕事ではなく、|美術に|関わる|用件だった。||前日の|午後、|ヴァンスは|行きつけの|画廊で|開かれた、|<セザンヌ>の|内覧会に|出かけ、|どうしても|手に入れたい|絵を|いくつか|見つけたらしい。||その|購入手続きを|私に|依頼する|ために、|彼は|わざわざ|朝早い|食卓に|私を|招いたのである。

A word concerning my relationship with Vance is necessary to clarify my rôle of narrator in this chronicle.

ここで|この記録の|語り手としての|私の|立場を|明らかに|するために、|私と|ヴァンスとの|関係|について、|一言|触れておく|必要が|あるだろう。

The legal tradition is deeply imbedded in my family, and when my preparatory-school days were over, I was sent, almost as a matter of course, to Harvard to study law. It was there I met Vance, a reserved, cynical and caustic freshman who was the bane of his professors and the fear of his fellow-classmen. Why he should have chosen me, of all the students at the University, for his extra-scholastic association, I have never been able to understand fully.

私の|家系は|法律家の|伝統が|深く|根付いており、|法科大学への|進学校を|卒業すると、|当然の|ように|<ハーバード|大学>へ|進み、|法律を|学ぶことに|なった。||そこで|出会ったのが|ヴァンス|だった。||彼は|内向的で|皮肉っぽく、|棘のある|口ぶりの|新入生で、|教授たちに|とっては|頭痛の|種であり、|同級生|たちに|とっては|恐れられる|存在だった。||なぜ、|大学じゅうの|学生の|中から、|こともあろうに|私を|学外での|友人に|選んだのか、|その|理由は|今なお|完全には|理解できない。

My own liking for Vance was simply explained: he fascinated and interested me, and supplied me with a novel kind of intellectual diversion. In his liking for me, however, no such basis of appeal was present.

I was (and am now) a commonplace fellow, possessed of a conservative and rather conventional mind. But, at least, my mentality was not rigid, and the ponderosity of the legal procedure did not impress me greatly—which is why, no doubt, I had little taste for my inherited profession—; and it is possible that these traits found certain affinities in Vance’s unconscious mind. There is, to be sure, the less consoling explanation that I appealed to Vance as a kind of foil, or anchorage, and that he sensed in my nature a complementary antithesis to his own. But whatever the explanation, we were much together; and, as the years went by, that association ripened into an inseparable friendship.

私|自身が、|ヴァンスに|惹かれた|理由は|単純だった。||彼の|個性は、|私の|興味を|かき立て、|これまでにない|知的な|刺激を|私に|与えて|くれたのである。||だが、|彼が|私に|好意を|持った|理由は、|私の|そういった|魅力に|よるものでは|なかったと|思う。

私は|今も|なお、|ごく|平凡な|男で、|保守的で|かなり|常識的な|頭の|持ち主に|すぎない。||ただ、|少なくとも|凝り固まった|考えを|持っている|わけでは|なく、|法律の|手続きを|深く|考える|ことには|あまり|関心が|なかった。||だからこそ、|私は|父親と|同じ|職業に|大した|興味を|持てなかった。||おそらく|そうした|性格が、|ヴァンスの|無意識の|中で|何らかの|類似性を|感じたのだろう。||いや、|もっと|慰めに|ならない|説明として、|彼にとって|私は|一種の|比較対象、|あるいは|単なる|『標準』とか|『拠り所』のような|存在であり、|彼の|本性に|対して、|何か|補完できる|反対要素|としての|価値を|見いだして|いただけ|かもしれない。||だが|理由は|どうあれ、|私たちは|しばしば|行動を|共にし、|年を|重ねるうちに|その|交流は|切り離せぬ|関係へと|育っていった。

Upon graduation I entered my father’s law firm—Van Dine and Davis—and after five years of dull apprenticeship I was taken into the firm as the junior partner. At present I am the second Van Dine of Van Dine, Davis and Van Dine, with offices at 120 Broadway.

At about the time my name first appeared on the letter-heads of the firm, Vance returned from Europe, where he had been living during my legal novitiate, and, an aunt of his having died and made him her principal beneficiary, I was called upon to discharge the technical obligations involved in putting him in possession of his inherited property.

大学卒業後、|私は|父が|友人と|共同経営|している|法律事務所に|入り、|5年間の|退屈な|見習い|期間を|過ごして、|ようやく|3人目の|共同経営者に|迎え入れられた。||今では、|父に|次ぐ、|第二の|ヴァンダインとして、|<ブロードウェイ|120番地>に|事務所を|構えている。

ちょうど|私の|名前が、|事務所の|専用封筒に|初めて|載るように|なったころ、|ヴァンスは|ヨーロッパから|帰国した。||彼は、|私の|弁護士|見習いの|あいだ、|海外に|滞在|していたが、|ちょうど|その頃に|叔母が|亡くなり、|遺産の|大部分を|彼に|残したのである。||私は|その|手続きを|引き受け、|ヴァンスが|相続|財産を|正式に|受け取れる|ようにした。

This work was the beginning of a new and somewhat unusual relationship between us. Vance had a strong distaste for any kind of business transaction, and in time I became the custodian of all his monetary interests and his agent at large. I found that his affairs were various enough to occupy as much of my time as I cared to give to legal matters, and as Vance was able to indulge the luxury of having a personal legal factotum, so to speak, I permanently closed my desk at the office, and devoted myself exclusively to his needs and whims.

この出来事は、|私たちの|間に|新しく、|やや|風変わりな|関係が|始まる|きっかけと|なった。||ヴァンスは|あらゆる|種類の|事務処理を|ひどく|嫌っており、|やがて|私は|彼の|財産関係|一切を|預かる|管財人、|そして|いわば|彼の|専属の|代理人と|なった。

彼の|事務は、|あらゆる|分野に|わたっていたので、|私が|法律事務所の|仕事に|充てようと|していた|時間を、|全て|使ってしまう|ほどで|あった。||そして|ヴァンスは、|いわば、|個人で|法律顧問を|雇えるほどの|贅沢が|できる|身分に|あったので、|私は|事務所の|机を|永久に|しまっておいて、|彼の|依頼と|気まぐれに|専念|することに|したのである。

If, up to the time when Vance summoned me to discuss the purchase of the Cézannes, I had harbored any secret or repressed regrets for having deprived the firm of Van Dine, Davis and Van Dine of my modest legal talents, they were permanently banished on that eventful morning; for, beginning with the notorious Benson murder, and extending over a period of nearly four years, it was my privilege to be a spectator of what I believe was the most amazing series of criminal cases that ever passed before the eyes of a young lawyer. Indeed, the grim dramas I witnessed during that period constitute one of the most astonishing secret documents in the police history of this country.

もし|私が、|共同経営の|法律事務所から|身を引いた|ことで、|自分の|ささやかな|才能を|使う|場を|失ったことに|対して、|実は|後悔の念を|抱いていた|としよう。||しかし、|セザンヌの|購入に|ついて|話し合う|ために、|ヴァンスが|私を|呼び寄せた|ことから、|その|運命の|日の|朝、|後悔の念は、|永久に|消え去ったと|言っていい。

なぜなら、|あの|悪名高き、|ベンスン|殺人事件を|皮切りに、|ほぼ|4年に|わたって、|私のような|若き|弁護士には、|お目にかかる|ことは|できないはずの、|驚くべき|一連の|犯罪事件の|目撃者|となる|特権を|得たからである。||実際、|私が|その間に|目にした、|数々の|ぞっとする|ような|事件は、|この国の|犯罪史に|おける|最も|驚くべき|秘密文書の|一つ|として|看做されて|いるに|違いない。

Of these dramas Vance was the central character. By an analytical and interpretative process which, as far as I know, has never before been applied to criminal activities, he succeeded in solving many of the important crimes on which both the police and the District Attorney’s office had hopelessly fallen down.

これらの|事件の|主役は|ヴァンス|だった。||彼は、|少なくとも|私の|知る限り、|これまで|犯罪捜査に|適用|されたことが|ない、|分析|かつ|解釈する|方法に|よって、|警察も|地方検事局も|完全に|お手上げと|なっていた|数々の|重大事件を|解決|したのである。

Due to my peculiar relations with Vance it happened that not only did I participate in all the cases with which he was connected, but I was also present at most of the informal discussions concerning them which took place between him and the District Attorney; and, being of methodical temperament, I kept a fairly complete record of them. In addition, I noted down (as accurately as memory permitted) Vance’s unique psychological methods of determining guilt, as he explained them from time to time.

ヴァンスとの|特別な|関係の|おかげで、|私は|彼が|関わった|事件の|すべてに|同席した|ばかりでなく、|地方検事との|間で|交わされた|普段の|議論の|多くに|居合わせる|ことが|できた。||そして|几帳面な|性分ゆえに、|その経緯を|ほぼ|完全に|記録してきた。

さらに、|記憶の|及ぶかぎり|正確に、|ヴァンスが|時折|説明して|くれた、|犯罪を|解明する|独特の|心理的な|手法を|書きとめていた。

It is fortunate that I performed this gratuitous labor of accumulation and transcription, for now that circumstances have unexpectedly rendered possible my making the cases public, I am able to present them in full detail and with all their various side-lights and succeeding steps—a task that would be impossible were it not for my numerous clippings and adversaria.

この|金に|ならない|労働と|その記録を|続けてきた|ことは|幸いであった。||というのも、|今や|思いがけない|事情によって|これらの|事件を|公に|できる|こととなり、|細かい|ところや|その経過、|及び、|周辺事情を|詳しく|発表|することが|できるからである。 ||もし|膨大な|新聞の|切り抜きや|日記が|なかったならば、|とても|実現|できなかっただろう。

Fortunately, too, the first case to draw Vance into its ramifications was that of Alvin Benson’s murder.

Not only did it prove one of the most famous of New York’s causes célèbres, but it gave Vance an excellent opportunity of displaying his rare talents of deductive reasoning, and, by its nature and magnitude, aroused his interest in a branch of activity which heretofore had been alien to his temperamental promptings and habitual predilections.

さらに|幸運な|ことに、|ヴァンスを|初めて|その|世界へと|引き込んだ|事件が、|<アルヴィン=ベンスン|殺人事件>だった。

それは|ニューヨークの|有名な|『世間の|注目を|集める|事件』の|ひとつと|なったばかりか、|ヴァンスに、|その|特殊な|推理の|才能を、|存分に|発揮する|機会を|与え、|これまで、|彼の|気まぐれな|えり好みする|性格からは|縁遠かった|分野に、|その|性質と|重要性から、|彼は|強く|興味を|惹かれることに|なったのである。

The case intruded upon Vance’s life suddenly and unexpectedly, although he himself had, by a casual request made to the District Attorney over a month before, been the involuntary agent of this destruction of his normal routine.

その事件は、|突然|予期せず、|ヴァンスの|生活に|入り込んできた。||もっとも|ひと月あまり|前に、|ヴァンス|自身が|地方検事に|ちょっとした|依頼を|したのが|きっかけで、|いつもの|暮らしが|思いがけず|崩れることに|なったのである。

The thing, in fact, burst upon us before we had quite finished our breakfast on that mid-June morning, and put an end temporarily to all business connected with the purchase of the Cézanne paintings. When, later in the day, I visited the dsdsKessler Galleries, two of the water-colors that Vance had particularly desired had been sold; and I am convinced that, despite his success in the unravelling of the Benson murder mystery and his saving of at least one innocent person from arrest, he has never to this day felt entirely compensated for the loss of those two little sketches on which he had set his heart.

それは|実際には、|六月|半ばの|朝、|わたしたちが|まだ、|朝食の|片づけを|していた|ところに|突然|降りかかり、|セザンヌの|絵を|買う|話は|しばらく|棚上げと|なってしまった。||その日の|午後に、|私が|その|画廊を|のぞいた|ときには、|ヴァンスが|とりわけ|欲しがっていた|水彩画の|二枚は、|すでに|売れて|しまって|いた。||ベンスン|殺人事件の|なぞを|見事に|解き明かし、|罪なき者を|救った|手柄にも|かかわらず、|彼は|いまなお、|その|二枚の|小さな|スケッチ画を|逃したことを|完全に|埋め合わせ|できたとは|思っていない|ようだ。

As I was ushered into the living-room that morning by Currie, a rare old English servant who acted as Vance’s butler, valet, major-domo and, on occasions, specialty cook, Vance was sitting in a large armchair, attired in a surah silk dressing-gown and grey suède slippers, with Vollard’s book on Cézanne open across his knees.

その朝、|私は|<カーリー>に|案内されて|部屋に|入った。||カーリーは、|古風な|イギリスの|使用人で、|執事で、|主人の|身の回りの|世話係で、|屋敷の|管理人で、|ときには|食事の|世話までする|めったに|見かけない|なんでも|できる|男だった。

ヴァンスは、|大きな|肘掛け椅子に|腰を|おろし、|光沢のある|絹の|ガウンを|軽く|ひっかけ|灰色の|スエードの|スリッパを|履いて、|膝の|上には|セザンヌの|画集を|広げていた。

“Forgive my not rising, Van,” he greeted me casually. “I have the whole weight of the modern evolution in art resting on my legs. Furthermore, this plebeian early rising fatigues me, y’ know.”

「座ったままで|失礼、|ヴァン。」

ヴァンスは|気軽に|声を|かけた。

「近代美術の|進化の|重要性が、|いま|この|両脚に|のしかかって|いるんだ。||それに|この|庶民的な|早起き|というやつは、|どうにも|身に|こたえる」

He riffled the pages of the volume, pausing here and there at a reproduction.

“This chap Vollard,” he remarked at length, “has been rather liberal with our art-fearing country. He has sent a really goodish collection of his Cézannes here. I viewed ’em yesterday with the proper reverence and, I might add, unconcern, for Kessler was watching me; and I’ve marked the ones I want you to buy for me as soon as the Gallery opens this morning.”

He handed me a small catalogue he had been using as a book-mark.

彼は|本を|ぱらぱらと|めくりながら、|ところどころで|複製画に|目をとめた。

「この|内覧会を|開いた|人|というのは。」

しばらくして|彼は|言った。

「芸術を|恐れる|我が国に、|ずいぶん|気前よく|贈りものを|してくれたよ。||立派な|セザンヌの|数々を|運んできて|くれたんだ。||昨日、|私は|その絵を|それなりの|敬意を|払って|鑑賞した。||ちなみに、|画廊の|主人に|見張られて|いたが、|私は|平然と|していたよ。||そして|今朝、|画廊が|開いたら、|君に|頼もうと|思って、|欲しいものに|印を|つけておいた。」

彼は、|それまで|しおり代わりに|使っていた|小さな|カタログを|私に|手渡した。

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー「芸術を恐れるアメリカ」について💁

“A beastly assignment, I know,” he added, with an indolent smile.

“These delicate little smudges with all their blank paper will prob’bly be meaningless to your legal mind—they’re so unlike a neatly-typed brief, don’t y’ know.

And you’ll no doubt think some of ’em are hung upside-down,—one of ’em is, in fact, and even Kessler doesn’t know it.

But don’t fret, Van old dear. They’re very beautiful and valuable little knickknacks, and rather inexpensive when one considers what they’ll be bringing in a few years.

Really an excellent investment for some money-loving soul, y’ know—inf’nitely better than that Lawyer’s Equity Stock over which you grew so eloquent at the time of my dear Aunt Agatha’s death.”1

「つまらない|雑用を|頼んで|いるのは|わかってるよ」と、|彼は|のんびりとした|笑みを|浮かべながら|そう|付け加えた。

「この|余白ばかりの、|掠れたような|小さな|スケッチなんか、|法律家の|きみには|たぶん|意味|不明だろう。||きちんと|タイプされた|裁判書類とは|まるで|違うからね。||これなんか|きみには|逆さに|掛けられて|いるように|見えるだろう。||実際、|ひとつは|本当に|逆さま|なんだよ。||しかも、|そのことに|主人でさえ|気づいて|いないんだ。||まあ、|心配|することは|ないよ、|ヴァン。||これらは|とても|美しくて|価値のある|小品で、|数年後に|どれだけ|値打ちが|出るかを|思えば、|むしろ|安い|買い物|なんだ。||本当に|金を|儲けたい|人間に|とっては、|実に|優れた|投資だよ。||伯母の|<アガサ>が|亡くなった|とき、|君が|やけに|熱弁を|振るっていた|<弁護士|おすすめの|株>|なんかより、|はるかに|ましだね。」

Vance’s one passion (if a purely intellectual enthusiasm may be called a passion) was art—not art in its narrow, personal aspects, but in its broader, more universal significance.

And art was not only his dominating interest, but his chief diversion.

He was something of an authority on Japanese and Chinese prints; he knew tapestries and ceramics; and once I heard him give an impromptu causerie to a few guests on Tanagra figurines, which, had it been transcribed, would have made a most delightful and instructive monograph.

ヴァンスが|唯一、|情熱を|傾けた|対象(もっとも、|それを|情熱と|呼んで|よければの|話だが)は|芸術|だった。||芸術は、|彼にとって|最大の|関心事と|いうだけでなく、|何よりの|楽しみでも|あった。||日本や|中国の|版画に|ついては、|素人離れ|した|知識を|もっていた。

Vance had sufficient means to indulge his instinct for collecting, and possessed a fine assortment of pictures and objets d’art.

His collection was heterogeneous only in its superficial characteristics: every piece he owned embodied some principle of form or line that related it to all the others.

One who knew art could feel the unity and consistency in all the items with which he surrounded himself, however widely separated they were in point of time or métier or surface appeal.

Vance, I have always felt, was one of those rare human beings, a collector with a definite philosophic point of view.

ヴァンスは、|蒐集欲を|十分に|満たせるほどの|余裕があり、|優れた|絵画や|美術|工芸品を|所有していた。||彼の|コレクションは|一見すると|バラバラに|見えたが、|所有する|どの|作品にも|形や|線の|上で|共通する|法則に|則っており、|それが|他の|作品|すべてと|つながりを|もっていた。

私は|いつも|感じて|いたのだが、|ヴァンスは|稀に見る|存在で、|明確な|哲学的|視点を|備えた|蒐集家で|あった。

His apartment in East Thirty-eighth Street—actually the two top floors of an old mansion, beautifully remodelled and in part rebuilt to secure spacious rooms and lofty ceilings—was filled, but not crowded, with rare specimens of oriental and occidental, ancient and modern, art.

His paintings ranged from the Italian primitives to Cézanne and Matisse; and among his collection of original drawings were works as widely separated as those of Michelangelo and Picasso.

Vance’s Chinese prints constituted one of the finest private collections in this country. They included beautiful examples of the work of Ririomin, Rianchu, Jinkomin, Kakei and Mokkei.

<ニューヨーク|東|38丁目>に|ある|彼の|住まいは、|古い|邸宅の|二階と|三階を|使い、|広々とした|部屋と|高い|天井を|確保|するために|美しく|改装され、|一部は|改築|されていた。||東洋と|西洋、|古代から|現代に|いたる|希少な|美術品で|一杯だったが、|それは|決して|雑然と|している|ようには|見えなかった。

“The Chinese,” Vance once said to me, “are the truly great artists of the East. They were the men whose work expressed most intensely a broad philosophic spirit.

By contrast the Japanese were superficial. It’s a long step between the little more than decorative souci of a Hokusai and the profoundly thoughtful and conscious artistry of a Ririomin.

Even when Chinese art degenerated under the Manchus, we find in it a deep philosophic quality—a spiritual sensibilité, so to speak.

And in the modern copies of copies—what is called the bunjinga style—we still have pictures of profound meaning.”

Vance’s catholicity of taste in art was remarkable. His collection was as varied as that of a museum.

It embraced a black-figured amphora by, a proto-Corinthian vase in the Ægean style, Koubatcha and Rhodian plates, Athenian pottery, a sixteenth-century Italian holy-water stoup of rock crystal, pewter of the Tudor period (several pieces bearing the double-rose hall-mark), a bronze plaque by Cellini, a triptych of Limoges enamel, a Spanish retable of an altar-piece by Vallfogona, several Etruscan bronzes, an Indian Greco Buddhist, a statuette of the Goddess Kuan Yin from the Ming Dynasty, a number of very fine Renaissance wood-cuts, and several specimens of Byzantine, Carolingian and early French ivory carvings.

ヴァンスの|美術の|趣味は|注目すべき|ものであった。||彼の|コレクションは、|博物館に|匹敵|するほど|多岐に|わたっていた。

His Egyptian treasures included a gold jug from Zakazik, a statuette of the Lady Nai (as lovely as the one in the Louvre), two beautifully carved steles of the First Theban Age, various small sculptures comprising rare representations of Hapi and Amset, and several Arrentine bowls carved with Kalathiskos dancers.

On top of one of his embayed Jacobean book cases in the library, where most of his modern paintings and drawings were hung, was a fascinating group of African sculpture—ceremonial masks and statuette-fetishes from French Guinea, the Sudan, Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, and the Congo.

図書室では、|近代絵画や|デッサンの|大部分が|壁に|掛けられていた。

A definite purpose has animated me in speaking at such length about Vance’s art instinct, for, in order to understand fully the melodramatic adventures which began for him on that June morning, one must have a general idea of the man’s penchants and inner promptings. His interest in art was an important—one might almost say the dominant—factor in his personality. I have never met a man quite like him—a man so apparently diversified, and yet so fundamentally consistent.

ヴァンスの|芸術的な|こだわりに|ついて|語ったのは、|明確な|理由があるからだ。||というのも、|あの|六月の|朝から|彼に|降りかかった|劇的な|冒険を|十分に|理解する|ためには、|彼の|好みや|考え方に|ついて、|一般的な|認識を|持っておかねば|ならないからだ。

芸術への|関心は、|彼の|性格に|おける|重要な、|いや、|むしろ|支配的な|要素であった。||私は|彼のような|人物に|出会った|ことがない。||外見は|きわめて|多様に|見えながら、|基本的には|驚くほど|一貫性を|保っていた|人間|なのだ。

Vance was what many would call a dilettante. But the designation does him injustice.

He was a man of unusual culture and brilliance.

An aristocrat by birth and instinct, he held himself severely aloof from the common world of men.

In his manner there was an indefinable contempt for inferiority of all kinds.

The great majority of those with whom he came in contact regarded him as a snob. Yet there was in his condescension and disdain no trace of spuriousness.

ヴァンスは、|多くの|人々が|道楽者と|呼ぶであろう|人物だった。||だが|その|呼び方は|彼を|不当に|貶める|ものである。

彼は|並外れた|教養と|知性を|備えていた。||生まれも|性格も|根っからの|上流|階級であり、|庶民的な|世界からは|厳しく|距離を|置いていた。

彼の|態度には、|知性や|美的|感覚を|欠いた|あらゆる|ものを|軽蔑|しているのが|見てとれた。

そのため|彼と|接する|大多数の|人々は、|彼を|紳士ぶった|鼻持ち|ならない|男だと|みなした。||だが、|その|相手を|見下し|軽蔑する|態度には、|わざとらしい|ところは|少しも|なかった。

His snobbishness was intellectual as well as social.

He detested stupidity even more, I believe, than he did vulgarity or bad taste. I have heard him on several occasions quote Fouché’s famous line: C’est plus qu’un crime; c’est une faute. And he meant it literally.

彼の|人を|見下す|性格は、|人間|関係|だけでなく|知性の|面にも|あらわれていた。||ヴァンスは、|下品さや|悪趣味よりも|愚かさを|嫌って|いたのだと|思う。

Vance was frankly a cynic, but he was rarely bitter: his was a flippant, Juvenalian cynicism.

Perhaps he may best be described as a bored and supercilious, but highly conscious and penetrating, spectator of life. He was keenly interested in all human reactions; but it was the interest of the scientist, not the humanitarian.

Withal he was a man of rare personal charm. Even people who found it difficult to admire him, found it equally difficult not to like him.

His somewhat quixotic mannerisms and his slightly English accent and inflection—a heritage of his post-graduate days at Oxford—impressed those who did not know him well, as affectations. But the truth is, there was very little of the poseur about him.

彼の|どこか|風変わりな|仕草や、|<オックスフォード|大学>での|大学院|時代に|身につけた|軽い|イギリス風の|アクセントや|抑揚は、|彼を|よく|知らない|人たちには|わざとらしく|映った。||だが|実際の|ところ、|彼の|中に|気取ったような|ところは|ほとんど|なかった。

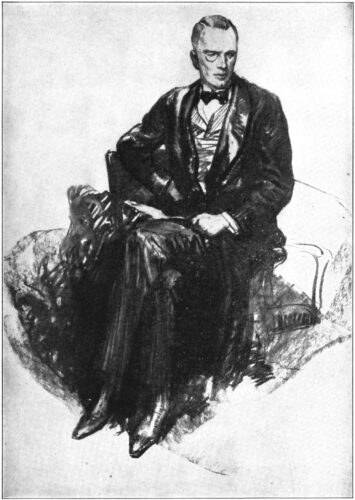

He was unusually good-looking, although his mouth was ascetic and cruel, like the mouths on some of the Medici portraits2; moreover, there was a slightly derisive hauteur in the lift of his eyebrows.

彼は|ひときわ|容貌に|恵まれて|いたが、|口もとには|禁欲的な|冷たさがあり、|また、|眉を|わずかに|上げたときに、|やや|人を|あざけるような|高慢さが|あった。

Despite the aquiline severity of his lineaments his face was highly sensitive. His forehead was full and sloping—it was the artist’s, rather than the scholar’s, brow. His cold grey eyes were widely spaced. His nose was straight and slender, and his chin narrow but prominent, with an unusually deep cleft.

When I saw John Barrymore recently in Hamlet I was somehow reminded of Vance; and once before, in a scene of Cæsar and Cleopatra played by Forbes-Robertson, I received a similar impression.3

鷲のように|鋭い|目鼻立ちで|ありながら、|その|表情は|きわめて|繊細だった。||額は|広く|斜めに伸び、|学者と|いうより|芸術家に|近かった。||冷ややかな|灰色の|目は|大きく|離れており、|鼻は|真っすぐで|細く、|顎は|狭いながらも|突き出し、|深い|割れ目が|走っていた。|

Vance was slightly under six feet, graceful, and giving the impression of sinewy strength and nervous endurance.

He was an expert fencer, and had been the Captain of the University’s fencing team. He was mildly fond of outdoor sports, and had a knack of doings things well without any extensive practice. His golf handicap was only three; and one season he had played on our championship polo team against England. Nevertheless, he had a positive antipathy to walking, and would not go a hundred yards on foot if there was any possible means of riding.

ヴァンスの|背丈は|六フィート(約183センチ)に|わずかに|届かぬほどで、|しなやかで|強靭な|筋肉と|精神的な|我慢強さを|思わせる|体つきを|していた。

フェンシングの|達人であり、|大学の|フェンシングチームの|主将を|務めた|こともある。||野外|スポーツも|嫌いではなく、|熱心な|練習を|しなくても|何ごとも|器用に|こなした。

ゴルフの|ハンディキャップは|わずかに|三で、|一度は|全米選手権の|ポロチームに|入り、|イギリスと|対戦|したことも|あった。||それでも|歩くことには|強い|嫌悪感を|抱き、|もし|乗り物が|利用|できるなら|百ヤードの|道のりでさえ|歩こうとは|しなかった。

In his dress he was always fashionable—scrupulously correct to the smallest detail—yet unobtrusive. He spent considerable time at his clubs: his favorite was the Stuyvesant, because, as he explained to me, its membership was drawn largely from the political and commercial ranks, and he was never drawn into a discussion which required any mental effort.

He went occasionally to the more modern operas, and was a regular subscriber to the symphony concerts and chamber-music recitals.

服装は|常に|流行を|追い、|細かい|ところまで|完璧で|ありながら、|決して|でしゃばっては|いなかった。||上流階級の|集う|クラブに|足を|運ぶ|時間も|多く、|とりわけ|<ステュイヴサント=クラブ>を|好んだ。||というのも、|そこの|会員は|主に|政界や|経済界の|人々で|構成|されているので、|頭を|使う|議論には|ならないからと|私に|説明|してくれた。

現代的な|オペラを|ときおり|鑑賞し、|交響楽や|室内楽の|定期会員|でもあった。

Incidentally, he was one of the most unerring poker players I have ever seen.

I mention this fact not merely because it was unusual and significant that a man of Vance’s type should have preferred so democratic a game to bridge or chess, for instance, but because his knowledge of the science of human psychology involved in poker had an intimate bearing on the chronicles I am about to set down.

ちなみに、|彼は|私が|これまでに|見た|中で、|最も|間違いの|少ない|ポーカーの|名手の|一人だった。

この事実を|私が|引き合いに|出したのは、|ヴァンスの|ような|男が、|ブリッジや|チェスよりも|極めて|庶民的な|ゲームを|好んだことが|異例で|重要だから|というわけでは|ない。||例えば、|彼が|ポーカー|という|人間心理学の|分野に|通じて|いたことが、|これから|記す|記録に|深い|かかわりを|持つからだ。

Vance’s knowledge of psychology was indeed uncanny. He was gifted with an instinctively accurate judgment of people, and his study and reading had co-ordinated and rationalized this gift to an amazing extent.

He was well grounded in the academic principles of psychology, and all his courses at college had either centered about this subject or been subordinated to it. While I was confining myself to a restricted area of torts and contracts, constitutional and common law, equity, evidence and pleading, Vance was reconnoitring the whole field of cultural endeavor.

He had courses in the history of religions, the Greek classics, biology, civics and political economy, philosophy, anthropology, literature, theoretical and experimental psychology, and ancient and modern languages.4 But it was, I think, his courses under Münsterberg and William James that interested him the most.

ヴァンスの|心理学の|知識は、|まるで|魔法の|ようだった。

彼は、|生まれつき|人を|見抜く|正確な|判断力に|恵まれ、|研究と|解釈|によって、|その|能力を|整理し|理論として、|驚くほどの|域にまで|高めていた。

彼は、|心理学の|基本に|しっかりと|基礎を|持ち、|大学での|すべての|履修|科目は、|この|学科を|中心|とするか、|あるいは|それに|付随していた。

ヴァンスは|知的で|芸術的な|分野の|すべてを|探っていた。||宗教学、|古代ギリシャ、|生物学、|政治学や|経済学、|哲学、|人類学、|文学、|理論|および|実験心理学、|さらには|古代語から|現代語|までを|履修|していたのである。

Vance’s mind was basically philosophical—that is, philosophical in the more general sense.

Being singularly free from the conventional sentimentalities and current superstitions, he could look beneath the surface of human acts into actuating impulses and motives.

Moreover, he was resolute both in his avoidance of any attitude that savored of credulousness, and in his adherence to cold, logical exactness in his mental processes.

ヴァンスの|精神は、|いわゆる|哲学的|といって|いいだろう。||彼は|ありふれた|感傷や|流行から、|際立って|自由な|立場を|とっていたので、|人間の|表面的な|行為を、|裏で|動かしている|衝動や|動機を|見通すことが|できた。

さらに|彼は、|騙されやすい|人間と|見られない|ように|すること、|自分の|思考の|過程|においては、|冷静にして|論理的な|正確さを|守ること、|この|二つを|徹底|していた。

“Until we can approach all human problems,” he once remarked, “with the clinical aloofness and cynical contempt of a doctor examining a guinea-pig strapped to a board, we have little chance of getting at the truth.”

「我々は、|全ての|人間の|問題に|対してはね」と、|彼は|かつて|こう|述べた。

「まな板の|上の|鼠を|調べる|医者のように、|臨床的に|距離を|置き、|軽蔑|しながら|観察|することが|できるように|ならないと、|真実に|たどりつける|見込みは|ほとんど|ないんだ。」

Vance led an active, but by no means animated, social life—a concession to various family ties.

But he was not a social animal.—I can not remember ever having met a man with so undeveloped a gregarious instinct,—and when he went forth into the social world it was generally under compulsion.

ヴァンスは|活動的な|社会生活を|おくっては|いたが、|決して|生き生きとした|ものでは|なかった。||それは|いろいろな|親族関係に|配慮|したからである。

彼は|社交的な|人間では|なかった。||これほどまでに|社交性の|未熟な|人間に、|私は|いまだ|出会った|ことがない。||そして、|彼が|社交の|場に|出ていくのは、|たいてい|無理矢理に|呼ばれての|ことだった。

In fact, one of his “duty” affairs had occupied him on the night before that memorable June breakfast; otherwise, we would have consulted about the Cézannes the evening before; and Vance groused a good deal about it while Currie was serving our strawberries and eggs Bénédictine.

実のところ、|あの|6月の|忘れがたい|朝食の|前の|夜、|ヴァンスは|義務的な|付き合いで|忙しかった。||そうでなければ、|その晩に|セザンヌの|絵|について|相談|できていた|はずだ。||そして、|カーリーが|イチゴと|ハムエッグを|運んでいる|あいだ、|ヴァンスは|そのことを|かなり|ぶつぶつ|言っていた。

Later on I was to give profound thanks to the God of Coincidence that the blocks had been arranged in just that pattern; for had Vance been slumbering peacefully at nine o’clock when the District Attorney called, I would probably have missed four of the most interesting and exciting years of my life; and many of New York’s shrewdest and most desperate criminals might still be at large.

その後、|私は|『偶然|という|神様』に、|心からの|感謝の|気持ちを|捧げることに|なった。||もしも、|ちょうど|あのように|偶然の|組み合わせが|並んで|いなかったら、||九時に、|地方検事の<マーカム>が|呼びに|来たとき、|ヴァンスが|静かに|眠っていたら、|私は|おそらく|人生で|もっとも|おもしろく、|もっとも|刺激的な|4年間を|逃していたし、|ニューヨークの|もっとも|狡賢く、|もっとも|卑怯な|犯罪者の|連中が、|今なお|社会に|溢れていたに|違いない。

Vance and I had just settled back in our chairs for our second cup of coffee and a cigarette when Currie, answering an impetuous ringing of the front-door bell, ushered the District Attorney into the living-room.

ヴァンスと|私が、|二杯めの|珈琲と|たばこを|楽しもうと|椅子で|くつろいで|いたとき、|玄関の|呼び鈴が|激しく|鳴りひびいて、|カーリーが|それに|こたえて、|マーカムを|客間へと|案内してきた。

“By all that’s holy!” he exclaimed, raising his hands in mock astonishment.

“New York’s leading flâneur and art connoisseur is up and about!”

「なんだって!」と、|マーカムは|大袈裟に|両手を|上げて、|驚いて|みせた。

「ニューヨーク|いちの|怠け者で、|美術通の|ヴァンスが、|もう|起きているとは!」

“And I am suffused with blushes at the disgrace of it,” Vance replied.

「そんな|不名誉な|ことを|言われると、|私は|恥ずかしさで|一杯に|なってしまうよ」|と、|ヴァンスは|こたえた。

It was evident, however, that the District Attorney was not in a jovial mood. His face suddenly sobered.

“Vance, a serious thing has brought me here. I’m in a great hurry, and merely dropped by to keep my promise. . . . The fact is, Alvin Benson has been murdered.”

しかし、|マーカムが|明るい|気分では|ないことは、|明らかだった。||彼は|たちまち|真剣な|顔になった。

「ヴァンス、|実は|きわめて|重大な|ことが|あって、|ここに|来たんだ。||私は|約束が|あって|とても|急いでいるが|ちょっとだけ|立ち寄ったんだ。||実は、|<アルヴィン=ベンスン>が|殺されたのだ。」

Vance lifted his eyebrows languidly.

“Really, now,” he drawled.

“How messy! But he no doubt deserved it. In any event, that’s no reason why you should repine. Take a chair and have a cup of Currie’s incomp’rable coffee.”

And before the other could protest, he rose and pushed a bell-button.

ヴァンスは|気だるそうに|眉を|上げた。||「いやはや、|それはまた」|と、|彼は|ゆっくり|返事した。

「なんと|厄介な!||しかし|彼は|そうなって|当然|だろうな。||いずれにせよ|君が|悩むような|ことはないよ。||すわって|カーリーの|類稀なる|珈琲を|一杯|飲みたまえ。」

そして、|相手が|異論を|挟もうと|するまえに、|ヴァンスは|立ちあがり、|呼び鈴の|ボタンを|押した。

Markham hesitated a second or two.

“Oh, well. A couple of minutes won’t make any difference. But only a gulp.”

And he sank into a chair facing us.

マーカムは|少々|ためらった。

「まあ、|いいだろう。|二、三分なら|構わない。|だが、|一口だけだ。」

そう言うと、|私たちの|目の|前の|椅子に|ドサっと|腰を|おろした。